How should we [teach and] learn to design for ecological resilience?

[The we is us teachers and students of architecture, landscape, urban and environmental design. The making of new landscapes that contribute toward ecological resilience bit is where things get interesting.]

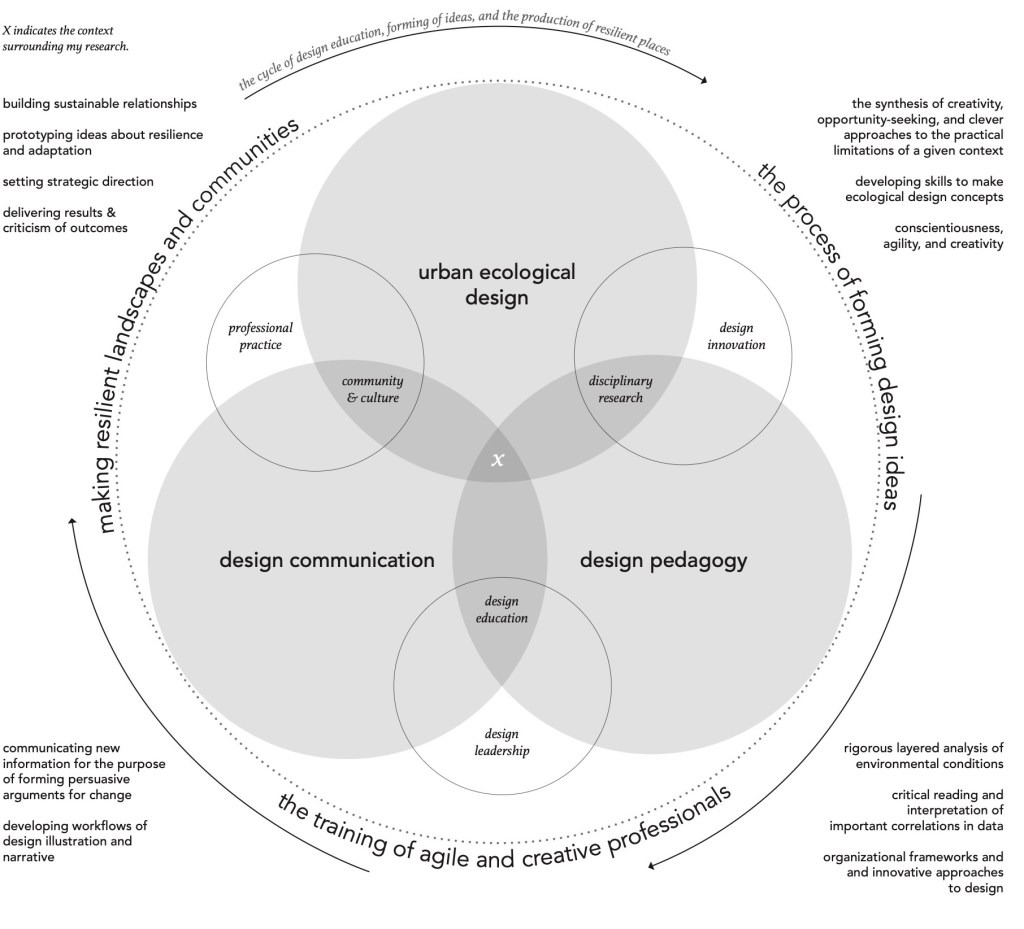

My principal areas of expertise are urban ecological design, design communication, and design pedagogy, with ongoing work centered on the intersection of these three distinct fields. They overlap through the study of how resilient design concepts take form [above].

My aim over time is to better understand and describe how landscape architects can be more optimally trained to produce compelling and ecologically sound design concepts. I have a hunch this will help create more beautiful places in the long run.

The building of resilient landscapes and communities requires agile, competent, and conscientious designers. They enter a highly competitive industry with professional licensure and evolving standards of practice, needing ever-increasing levels of creative and technical skills upon graduation. My work over the last two decades studies these factors by identifying and exploring the ways in which ecological design fundamentals are learned, communicated, and practiced. Focusing on how landscape architects can learn to design for ecological resilience, my research is organized around three main questions:

1. How do design concepts form?

2. How is design education evolving to prepare graduates for contemporary professional practice?

3. How can ecological design and design pedagogy inform one another?

Why?!

Because the world we live in is important. The places where we experience our lives shape us and our behavior, our relationships and opportunities. And why landscape architecture? Because of its capacity to analyze and act on that reality. It’s a proactive profession. And that’s not to say action is always required. Rather, that a process unfold to synthesize some creativity on one hand with the practical limitations of a given context on the other. A problem inspires the process of forming sometimes radical ideas, while the need to organize and communicate it for the purpose of forming a persuasive argument for change, requires us to focus differently. How these visionary qualities of ideation/ideas intersect with grounded forces of action offers a valuable line of inquiry, and one I believe is critical to the future of the discipline and profession. I will argue that thinking-big and communicating-well will be useful traits in the next generation of design practitioners and leaders. They’ve inherited a seemingly upended world, and yet if you sit with them and listen, you’ll learn that they, like you at their age, possess a prospective optimism. I recommend we give them room to work.

They know that to maintain relevance in the 21st century, the profession of landscape architecture will be required to develop more resilient design strategies and practices. Its practice will undergo technological revolutions unlike anything seen before in the coming years. As the field evolves from solely technical, functional, or purely aesthetic functions of the land, a more systematic approach that directly engages ecological and cultural conceptualization has become the norm. This work plays out on the public stage of rapidly evolving biological, economical, technical and political situations – embedded, entangled sites and issues, each reshaping the ways landscape architects operate and respond. The designers who will shape these future built environments in turn need to possess the skills and knowledge to practice an evolving discipline while adapting to changing conditions. This ongoing shift in design practice directly informs changes in design pedagogy and models of communication. Then there’s the work of making real places where people and nature can come together.

Cities across the globe are facing enormous growth pressure and competition as they struggle to evolve in ecological balance. The fragmented peri-urban and rural areas they are intimately linked to also face a host of serious concerns. The need for well-designed places – healthier, more humane, more accessible, current, dynamic public space – created within a framework of cultural and ecological heritage has arguably never been more acute. While some conventional approaches to design at the landscape scale tend to insert monofunctional or rigid infrastructural solutions, often prioritizing short-term economics over environmental factors, my work instead operates within frameworks of phenomenology, analysis and material exploration and through a combination of site reading, rigorous ideation and the integration of ecological principles of design.

By understanding and applying the fundamentals of ecology and design, my work aims to break down complex scenarios into legible patterns for the purposes of learning, educating, and affecting positive change. The production and increasing quality of my scholarship is fundamental to my capacity to create an optimal educational experience for my students. With an eye at once on making landscapes, learning about their culture and ecology, and describing their possible futures, my research can best be illustrated by defining its three principle themes.

Ecological Urban Design Practice, Pedagogy, and Communication

Design Practice:

I’ve been a design professional for more than twenty years. That experience in landscape architecture has taught me how to read and understand a wide range of design problems across multiple scales and levels of complexity. With some luck and heaps of friends and colleagues, I’ve been involved in numerous built and speculative projects around the globe. [Bussiere Portfolio] I opened LANDMASS, LLC when I arrived in Hawai’i in 2016 to engage with local projects in my neighborhood. My recent work includes concept design for the grounds at Pilihonua, a cultural education and community center, and gardens at the Vladimir Ossipoff Cabin up on Pālehua. I also serve as a licensed consultant on selected residential projects.

Other collaborative community-based design work includes ongoing efforts at Makalapa Park, through a UH NPS partnership that aims to grow its design from direct public participation. Four recently completed [UHCDC] projects with State and community agencies help me to frame the context this ongoing work, including, “Waipahu Ecological Assets, State Office of Planning”, “Kekaha Kai State Park Design Strategies, DLNR”, “Līhu‘e: In The Loop”, Public Realm Study and Urban Design, in Līhu‘e, Hawai‘i for The Mayors’ Institute on City Design and Kaua’i County, and “Varney Square: a UH Mānoa Campus Landscape Study and Redesign”. In demonstrating the impact these efforts have had on the State, DLNR Administrator Alan Carpenter who was my point of contact on Kekaha Kai, said about the work: “We’ve been very impressed by the ideas and the products that have come out of the UHCDC proof-of-concept efforts. Government agencies tend to be slow adopters of change and new technology. Tapping into digital-native student minds unfettered by bureaucracy has led to creative solutions with great potential. These concepts get further refined by faculty and project leaders into quality visuals, wonderfully rendered, which provide a great medium for staff to present to decision makers and advocate for full implementation.”

As a Principal Investigator at the University of Hawai‘i and University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center [UHCDC] I produced “An Ecotourism Model for Kekaha Kai State Park, Hawai`i Island”, presented in 2019 at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture [CELA] illustrated results of the 2018 funded project for the State Department of Land and Natural Resources [DLNR]. The 2017-2019 proof-of-concept study conceptualizes future programming and design for a cultural education facility and campground at the Hawaiʻi Island beach park. I also presented, “Kēkaha Kai, Hawaiʻi: a study in decarbonization and the poetics of remediation” at AsinaraLab023, III Convivium, The I Biennial of Resilience, Art & Landscape, an event of the XII Barcelona International Landscape Biennale.

In 2018, I was honored to join a team of distinguished Co-Principal Investigators to develop and publish the “Waipahu Transit Oriented Development Collaboration.” My contribution to the large-scale project included a 98-page Technical Report on Ecological Assets and Strategies for the State of Hawai‘i Office of Planning. The report studied existing ecological conditions in the community of Waipahu [peri-urban, TOD zoned] and proposed detailed projections and phased process to increase the existing urban tree canopy in partnership with the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife [DLNR DOFAW], Kaulunani Urban and Community Forestry Program, the City & County Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency, and Smart Trees Pacific. $250,000 was awarded for the collaborative project by the State, and the work has since been disseminated and recognized nationally, including the 2020 AIA/ACSA Practice + Leadership Award and ACSA Collaborative Practice Award, for “UHCDC Waipahu TOD Collaboration.”

Design Pedagogy:

As a kid, I’ll admit, I taught myself the majority of what I thought I should know. I couldn’t sit still long enough to understand what adults were saying anyway. And they didn’t look very happy or fulfilled, most of them, and I didn’t want to be like those folks. Instead, the old successional woods of central Massachusetts and a few brilliant mentors were my strange self-guided academy. They inspired me to want to know more, the forest and some wise elders. The schools, I treated as mere temporary prisons. I learned to read patterns and appreciate the slower, seemingly realer pace of nature. When it came time to take tests, I hacked them as best I could, rather than any sort of deep immersion into the content being “tested”. Anything to get back outside where learning could happen. Again, admittedly, I didn’t understand school. Yet, at the age of twenty six, I took a job as a professor and had to examine things more closely for the first time. I’ve been struggling with the same problem ever since. What is a school?!

Let’s start by defining one as a place where learning happens. Or more precisely, a place where learning can happen. Then we discover there are critical factors that help determine whether learning is in fact, happening. We’ll begin to recognize there are learning styles and habits that help to shape them. My learning occurs outside mostly, with a long view somewhere. Even still, the sun and wind; the atmosphere triggers a part of my brain differently than sitting indoors at a desk. Of course, this is true for everyone. Different, unique responses to diverse perceive stimuli, by each and every one of us. As a teacher now in my early forties, I get to learn in a lot of different ways, having so many opportunities to exchange and interact with the people around me. I’m blessed to work in a community of design educators, where we’re all searching for solutions to problems in the classroom and for ways to better understand and serve the needs of students.

My work in this area started small and has grown into some really meaningful discoveries, shared through multiple publications, including my book, Conceptual Landscapes: Fundamentals in the Beginning Design Process. Published in May 2023 by Routledge, Conceptual Landscapes is a vibrant and deliberate collection of critical perspectives I’ve organized over several years highlighting contemporary works, methods, and principles of conceptualization across the field of landscape architecture. Illustrated through a broad spectrum of work by leading experts, the book is tailored for students and focused on practical methods for spring-boarding into landscape design. Universally positive feedback received from the publisher and blind external reviews speak to the book’s contribution to discourse on contemporary landscape design. The book has been endorsed by highly regarded scholars, critics, and practitioners, including David Rubin, Chris Reed, Bradley Cantrell, and Timothy Schuler. Conceptual Landscapes is the culmination of several years of my immersion in design education, and a testament to my dedication to contributing to the future of the profession.

Stemming from a national survey I developed with Benjamin George of Utah State University, we’ve since co-authored two peer-reviewed articles and delivered two presentations centered on this research, first examining survey results across all student levels, in “Factors Impacting Students’ Decisions to Stay or Leave the Design Studio: A National Study”, then focusing on graduate and other non-traditional students. “Non-traditional Students and the Design Studio: Creating a Productive Learning Environment,” was recently published in Design Principles and Practices. [H-Index: 5; SJR Score: 0.102] This work aims squarely at an important gap in knowledge about the nature of this growing population of design students with the goal of understanding their evolving needs and finding opportunities for academic programs, administrators, and instructors to improve learning conditions in our studio environments. “Design and Experiential Learning in Post-Industrial Landscapes” was published in Landscape Research Record to describe outcomes of a study-abroad trip I led to Sardinia in 2015. And “Finding Space for Drawing: Blatant Observations and Latent Pedagogy” follows results of my ongoing development of a field drawing elective.

Design Communication:

Design communication [to me] is at its best a struggle between creativity and precision – between the search for new ideas for how we hope to see the world – and the visual acuity required to bring that world into being. How we share our stories is as important to me as how and what we think and make. Yet, as design educators, we often see students excited by the prospects of articulating a new idea, but nearly always struggling with the ambiguous beginning of each new project.

Designers tend to focus much of their efforts toward visual communication on making drawings and models as a way of rationalizing a-priori ideas. Instead, I’ve been exploring ways to encourage an emphasis on material experimentation as a critical stage of the process of conceptual discovery. I’ve shared this work in a collection of papers, exhibits, and presentations. My 2018 paper “Visual Ecologies: Natural Patterns in Conceptual Optics” for the Design Communications Association [DCA] discusses early exploratory outcomes of my Drawing Ecologies electives. In 2019 I presented “a-posteriori ecologies: models for engaged assembly” at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture [CELA] at UC Davis to further outline this effort with my co-author Lance Walters. I also presented my paper, “Landform and L’informe” at the National Conference on the Beginning Design Student [NCBDS] at Texas A&M University to advance the argument that tactile experimentation can lead to richer, deeper, and more tacit understanding of design conceptualization. My 2021 paper “In Search of the Big Idea” which was presented at the DCA describes how incremental growth allows students to build foundations in pursuit of more complex scenarios. I argue that the rational or logic based diagnosis of design opportunities within complex systems requires a stepwise, iterative and incremental trajectory.

By a stroke of luck, I was invited by curators the Italian Pavilion at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale to produce a short-film that focused on the resilience of the Hawaiian landscape. With a theme of “Resilient Communities” for the Italian Pavilion, I produced, wrote, and co-edited “Ho’omanawanui” with a team of artist collaborators to convey a simple but powerful story of how this landscape continues to adapt and rebound to pressure and environmental disturbance. Artist and Creative Director Ara Laylo directed the project. She shot the video content and edited a sequence we designed together. Ara also invited Keola Nakaʻahiki Rapozo, a Hawaiian cultural practitioner, graphic designer, and Director of Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi, an Oʻahu community-based non-profit where she shot the film, to develop a graphic identity for the project. He named it, Ho’omanawanui, which means, “to be patient, to be long-suffering, to make time longer, and to believe in things you know to preserve life.” Lala Nuss, the Climate Resilience and Equity Manager with the City & County of Honolulu’s Office of Climate Change, Sustainability and Resiliency [CCSR] was invited to narrate the film.

Ho’omanawanui presents a glimpse into the life of a family in Kākoʻo ʻŌiwi, a restored and operational lo’i in Heʻeia, as they talk story and play out the balance of planting and harvesting kalo. My essay for the film was published in the Biennalé Catalog, and according to the curator our film was viewed by tens of thousands of attendees. Since then, it’s been presented at multiple venues including the Venice Biennalé Symposium, MAYALAB, Resilient Communities, hosted by Landworks Circus [LWC], July 24, 2021 in Merida, Mexico, and at AsinaraLab021, in Asinara, Italy, September 14, 2019. I also presented the film and its background on our team’s behalf, with, “Hoʻomanawanui: Design, Patience and the Hawaiian landscape,” at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture in Spring 2022. The Conference Chairs said about the project, “We support acceptance of this submission as a strong demonstration of the potential for film as a tool of landscape research and design practice. The film clip is of high quality and thoughtfully depicts landscape relationships.” Outcomes of Hoʻomanawanui inspired a deeper more personal examination of the temporal qualities of built space in my most recent publication, “On Island Time, in Built Space”, an article under review for a Special Edition of the journal, Architecture. [2025]*